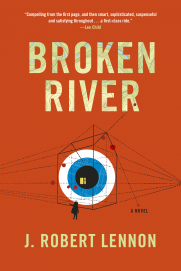

Broken River: A Novel

- By J. Robert Lennon

- Graywolf Press

- 240 pp.

- Reviewed by Amanda Holmes Duffy

- June 22, 2017

This haunted-house story gets too caught up in a misguided critique of the publishing industry.

J. Robert Lennon’s ninth novel, Broken River, begins with a mystery seen from a cinematic perspective. An unnamed Observer (with a capital O) watches a house in Upstate New York as its residents try to escape. There is a double murder, and the house becomes a crime scene. The Observer looks on dispassionately as everything unfolds, even as the house is forgotten, sits empty, and falls into disrepair.

Here, I was reminded of Jim Crace’s extraordinary novel Being Dead, which begins with the gradual decomposition of the bodies of two murder victims, described by an impassionate observer. In the same spirit, Broken River is off to a promising start.

Our Observer is attracted to “the negative spaces the people leave behind.” After a decade passes, a family from New York City moves into the house, and a new story begins. Karl, a sculptor, thinks of his work as “painting in three dimensions.” His wife, Eleanor, is a successful novelist. Their 12-year-old daughter, Irina, who is writing a book of her own, quickly becomes obsessed with the unsolved murders.

Then everything goes pear-shaped.

Karl, a charming hippie with a weakness for women, turns into a lazy stoner who can’t stop masturbating. Eleanor struggles with backaches and the effort to write from the heart. But neither of them cares about the other’s creative work. Karl has never read any of Eleanor’s books, and on a visit to MoMA, Eleanor decides that people who stand in front of paintings for minutes on end must be faking their interest. Meanwhile, Irina is left to her own devices. She befriends a girl at the ice cream parlor and imagines this girl to be the long-lost daughter of the murder victims.

The girls’ friendship flourishes. When, at one point, the two embrace, “It occurs to Irina that she has not been held, has not held another in quite this way in quite some time. This is the thing desired by the characters in Mother’s books: intimacy.”

And, indeed, the only true intimacy in this novel is between females who are relative strangers to each other. There’s Irina and her friend — and later, Eleanor, in an encounter with one of Karl’s lovers. The interactions between these characters are warm and compassionate.

But no such intimacy exists between the real partners in this novel. Sex comes down to fucking, and “family” is reduced to people in the same household who share computers. Irina’s music lessons are just an excuse for Karl to buy weed and meet a woman in a sleazy motel.

The most interesting passages in Broken River concern Eleanor’s writing process. “Her novel has been a constant companion to her anger and anxiety,” Lennon writes. She deletes paragraphs and then whole chapters.

“Once the book has been reduced to an invalid she began to build it back up into something new. A monster, nourished on internet cancer research, CyberSleuths, and mistress stalking. The book is about her marriage now, about the ways adults hurt children by being the assholes who love them. It’s about the way things you thought you put behind you can come back to kill you.”

Hang on. Isn’t this the book I’m reading? Except it sounds so much more passionate and angry than Broken River. Maybe this is the book that Lennon really wanted to write, until he lost heart and cynicism got in the way.

And what about the promise of those powerful opening chapters? What about the Observer, who has now been reduced to little more than a gimmick the author has grown tired of?

Then Lennon throws a slow pitch to his potential critics. An agent is talking about Eleanor’s new novel — the first of her books to take risks and actually mean something. “I think what we have here,” the agent says, “is a novel that shifts its focus. A novel that changes its identity midway…It’s uncertain of its aims.”

Toward the end of Broken River and the solved mystery that spurred it, Eleanor advises her daughter: “You need to work hard to get the good ideas. The old ideas weren’t bad, they just weren’t what the book wanted to be…All of the stories we tell ourselves are wrong. All of them.”

Armed with this insight, Irina writes the end of her own story. Except it isn’t very good. “She was trying to finish, and to enjoy finishing, even though she knew it was all wrong.”

That’s the writing process in a nutshell. Maybe it’s even a sad commentary on the publishing business. But reading should be a lot more enjoyable — and more effortless.

I tried to like this book. I wanted to be invested in the characters and in solving the mystery. But I’m not sure the author wanted me invested. I feel he was taking out his disappointments in the publishing industry on his readers. His characters were crass and two-dimensional. Was this the point? That the further in I got, the less I would care? Sadly, I suspect the author feels the same.

Amanda Holmes Duffy is the author of many short stories and a novel, I Know Where I Am When I’m Falling.