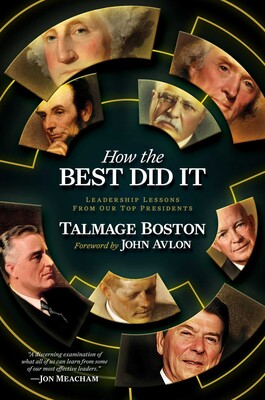

How the Best Did It: Leadership Lessons from Our Top Presidents

- By Talmage Boston

- Post Hill Press

- 400 pp.

- Reviewed by Andrew M. Mayer

- April 12, 2024

What can we learn from our ablest commanders-in-chief?

Texas lawyer/historian Talmage Boston has written in How the Best Did It a unique study of leadership centered on who he believes are America’s top eight presidents: George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, and Ronald Reagan. His list hews closely to C-SPAN’s 2021 Presidential Historians Survey, although he swaps out Harry S. Truman for Reagan.

Boston explores the leadership qualities of these commanders-in-chief and then broadens his lens to examine how anyone hoping to become a leader — whether in a major industry or a small community — can adopt those traits in order to overcome serious challenges and find success in their chosen field.

Washington is an obvious pick for any “greatest” list, but what makes him truly special, says the author, is that America’s premier Founding Father actually learned from his mistakes. As a young man, Washington had a volatile temper and exhibited excessive bravado in attempting to move up the military ladder in the French and Indian War and afterward. But he forced himself to calm down, listen, and take notes while a delegate in the Virginia House of Burgesses in the pre-Revolutionary War period. Boston credits Washington’s growing understanding of the power of nonverbal communication and embrace of a “less is more” approach to leading for his rise to commander of the Continental Army, head of the Constitutional Convention of 1787, and, finally, two-term president.

The author further praises Washington for his desire to avoid political infighting; his prioritizing of good governing above party fealty; and his insistence, foreign-policy-wise, that the U.S. remain neutral in the Napoleonic Wars.

Jefferson, inaugurated in 1801, took over at a time of U.S.-British strife stemming from the Alien and Sedition Acts put in place during John Adams’ presidency. He was determined to foster political harmony by holding weekly dinners with the opposition Federalists and hashing out key issues during frank, off-the-record discussions after the meal. He suffered in his second term due to the Embargo Act of 1807 but avoided war (something his successor, James Madison, failed to do in 1812). Jefferson is also lauded for his pivotal 1803 Louisiana Purchase, in which he paid Napoleon $15 million for a huge swath of land running from the Deep South to Oregon Country.

Lincoln is consistently named the best president in U.S. history for the way he guided the nation through the Civil War and ended slavery in America. He had a brilliant mind, writes Boston, and packed his cabinet with other brilliant minds. It’s likely that Lincoln would’ve coordinated a much more successful postwar Reconstruction than the one overseen by Andrew Johnson had not John Wilkes Booth ended his presidency and his life at Ford’s Theatre in April 1865.

The Roosevelts were cousins and shared similar characteristics. Theodore — who became president in 1901 upon William McKinley’s assassination — made his name by, among other things, taking on trusts and monopolies at home and ending the Russo-Japanese War abroad. Franklin entered the presidency in 1933 amid the Great Depression, and while he didn’t end it completely, he improved the economy and went on to helm a successful alliance against Nazi Germany in World War II. Both Roosevelts, Boston points out, overcame personal and political challenges, in part, thanks to strong wills and their assembling of strong cabinets.

Eisenhower, made famous in WWII, became president in 1953 during the McCarthy/Red Scare era and managed to avoid another global conflagration during his two terms. He was quiet but effective, explains the author, and knew when to play hardball.

Kennedy, though only in office 1,000 days before being assassinated in November 1963, guided America’s “New Frontier,” maintained a strong executive council, and applied the tough lessons learned during the Bay of Pigs disaster to successfully navigate 1962’s Cuban Missile Crisis. He also launched the space race, which would see the U.S. become the first nation to put a man on the moon, and he warmed considerably to the need for civil rights. The 1964 Civil Rights Act was set in motion partly by Kennedy’s evolving views on matters of race.

Reagan entered the White House in 1981 after a disastrous Jimmy Carter presidency plagued by oil embargoes, economic decline, and the Iran Hostage Crisis. He oversaw economic gains, and his opinion of the Soviet Union grew more nuanced after a series of summits with Mikhail Gorbachev, resulting in arms-control agreements between the superpowers. While the Cold War officially ended on George H.W. Bush’s watch, Reagan is largely credited with pulling off the feat.

Boston takes time at the end of each chapter to note the flaws — personal and professional — in his subjects but makes clear none of those faults prevented the men from reaching exemplar status. He is to be commended for making great use of many works by esteemed longtime presidential historians, as well as select primary sources, to create here a volume that will be useful both in the classroom and as a primer for future leaders in Washington, DC, and beyond.

Andrew M. Mayer is professor emeritus of humanities and history at the College of Staten Island/CUNY.