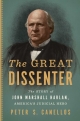

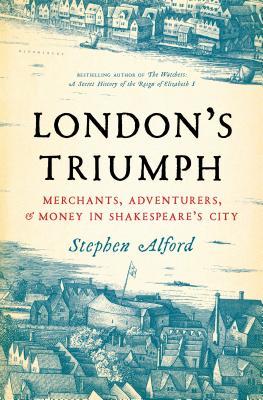

London’s Triumph: Merchants, Adventurers, and Money in Shakespeare’s City

- By Stephen Alford

- Bloomsbury USA

- 336 pp.

- Reviewed by Alice Padwe

- December 16, 2017

How a hamlet on the Thames unfurled its wings in the 16th century.

How did London rise from its position as a “modest satellite of a European system of international trade” in 1500 to a city boasting of commerce stretching to Russia, the Far East, and the New World by 1620?

In this book about “merchants, adventurers, and money,” historian Stephen Alford follows the careers of those whose successful (and occasionally failed) enterprises contributed to the power and prosperity of the city. He also provides background on the commercial scene in Tudor London and explains the paths to advancement in the city.

Little is known about the rise of some key figures. Anthony Jenkinson, navigator and negotiator, was the son of a rural innkeeper in Leicestershire. No records show how he found his way to the Ottoman Empire, but “in his early twenties, he had his own ship, men and cargo and Suleiman’s safe conduct.” About a decade later, Jenkinson was in Russia consolidating operations of an English trade enterprise, the Muscovy Company, and feasting as an honored guest of Ivan the Terrible.

Others did not spring from obscurity: Geographer and promoter of English colonies in the New World Richard Hakluyt was the ward of a successful barrister (also named Richard Hakluyt) who taught his young cousin about physical and political geography. Financier Thomas Gresham’s father, Richard, was a flourishing merchant who enjoyed the support of Cardinal Wolsey and Wolsey’s protégé, Thomas Cromwell.

Both Cromwell and the senior Gresham were involved with trade in the Low Countries, where Antwerp was a major commercial center. Richard Gresham, elected lord mayor of London and knighted, was eager to have an exchange building in London that would rival the Antwerp bourse. Although he did not live to see that building as his monument, his son Thomas, who, as Alford puts it, “was his father’s greatest legacy,” did.

Successfully negotiating terms for repayment of King Edward VI’s substantial debt, and nimbly going from the service of Protestant King Edward to Catholic Queen Mary after a brief hiatus, Thomas Gresham managed to get the magnificent Royal Exchange completed during the reign of Queen Elizabeth.

Thomas Gresham’s financial expertise and Jenkinson’s navigational ability started the two men on their respective paths, but without their excellent diplomatic and negotiating skills, neither would have achieved the success that helped London consolidate its gains.

Something of the spirit of these men can be seen in the name of one of the earliest trading companies: the Company of Merchant Adventurers, which began in the Middle Ages. The names of companies formed in the 16th and early 17th centuries demonstrate the increasing scope of London’s trade: the Muscovy Company, Turkey Company, Levant Company, Virginia Company, and East India Company.

In addition to those who ventured abroad, others who spent most of their lives in London were essential to the city’s growth. The scholarly resources and time-keeping devices of John Dee, as well as the maps and descriptions in Hakluyt’s three volumes of Principal Navigations, not only aided navigators but inspired investors.

Alford says he purposely kept famous names at the margins of his book, but without the royal charters and monopolies granted by the monarchs of the time, entrepreneurs would not have been able to negotiate trade agreements with foreign sovereigns. Queen Elizabeth, although known for her reluctance to open her purse, invested in some of the enterprises, including the slave trade.

Alford intersperses his accounts of these companies and the men who led them with descriptions of London, contrasting the glories of commercial success with the squalor and poverty of much of the city and its inhabitants.

He describes the spread of the city as its population rose from 50,000 in 1500 to 200,000 in 1600, and discusses problems arising from the influx of people from the English countryside and of those escaping religious warfare in Europe, as well as of the usual mix of foreign traders doing business in London.

The author devotes space to the change in attitude from the church prohibition of usury (with various methods of lending money to get around this) to the acceptance of what was instead called interest.

He points out that the partnership between commerce and government was essential for success. The folly of sailing abroad with dreams of riches in Cathay — without accurate knowledge of the land or ocean — is eventually replaced by successful voyages following the dissemination and publication of information gathered by voyagers.

The final chapter is primarily devoted to a cursory description of how London has changed since 1620. The author, whose earlier book was The Watchers: A Secret History of the Reign of Elizabeth I, seems much more comfortable in the Tudor and Jacobean city. His preceding chapters hold the reader’s attention more than do these pages that rush through the modern streets. It was those earlier sections that did, indeed, show that London between1500 and 1620 was “a place of formidable dynamism.”

Alice Padwe, who has edited books ranging from history texts to spy thrillers, and who enjoys reading books about London, would love to explore the city on foot more often.