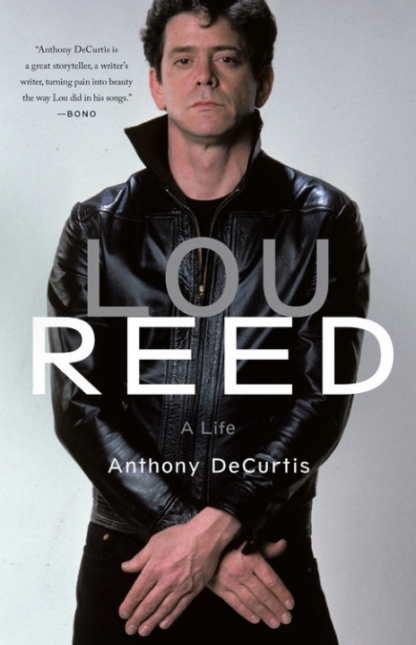

Lou Reed: A Life

- By Anthony DeCurtis

- Little, Brown and Company

- 528 pp.

- Reviewed by Michael Causey

- October 15, 2017

This well-balanced biography separates the man from the icon.

When Lou Reed’s now-classic “Sweet Jane” became a surprise hit, where was the man who had cavorted in Manhattan’s gay leather bars, later lived with a transvestite, and held court at the vanguard of what Tom Wolfe called the heroin chic?

Answer: Licking his wounds quietly in his parents’ Freeport, Long Island, house, working as a nine-to-five typist in his father’s accounting firm. I point this out not to make fun of Reed. Retreating to your family’s home in a time of crisis is nothing new. (I speak from experience.) But it’s illustrative of the opposing forces that dogged Reed until he died of liver disease in 2013. It wasn’t always easy to separate Lou Reed from “Lou Reed.”

Reed’s first serious band, the Velvet Underground, was undone by bad management and a cult status that marginalized them financially. Being a critic’s darling doesn’t pay the rent. After Reed left the seminal band to go solo, his work flicked at the lowest rung of the Billboard charts for a week or two before falling off the map. Desperate, he went back home and sought refuge with Mr. and Mrs. Reed.

Then came “Sweet Jane.” Buoyed by the attention, Reed transformed to “Reed” and moved back to Manhattan. The enfant terrible was back in action, mentally fencing with the likes of Andy Warhol, John Cale, and, later, performance artist Laurie Anderson. His third wife, Anderson was more than a match for Long Island’s bad boy.

Like Bob Dylan or Tom Waits, Reed didn’t exactly possess the voice of an angel; it’s hard to imagine any of them lasting long on “America’s Got Talent.” I’m not sure Heidi Klum would get it if Lou auditioned the great track “Dirty Boulevard” with his atonal vocal: “Give me your hungry, your tired, your poor, I’ll piss on ’em/that’s what the Statue of bigotry says/your poor huddled masses, let’s club ’em to death/and get it over with, and just dump ’em on the boulevard.” (Maybe Howard Stern would like it.)

“Lou doesn’t sing. He’s Lou,” an insightful Reed producer once remarked. It’s his lyrics that set him apart from the Kelly Clarksons of the world. At their best, they’re raw and honest with the keen observational, detached eye of a novelist. Poet Delmore Schwartz was an early idol.

Critics gravitate toward good lyricists for a simple reason: It gives them more to talk about. Pop-music scribes tend to give more ink and lavish a different kind of praise on a Lou Reed or an Elvis Costello than on a Paul McCartney or even the Rolling Stones.

Critics of the Stones tend to get as excited about their hedonistic lifestyle as their songwriting. It’s not exquisite poetry or Aeolic cadences that made “Start Me Up” a rock ’n’ roll classic. And how much can you say about a great pop song like Macca’s “Listen to What the Man Said” beyond calling it a great pop song? The lyrics don’t exactly invite deep discussion. Who is the man? What is he saying? I doubt Paul knows or even thought about it much.

Biographer and esteemed music critic Anthony DeCurtis knew Reed moderately well, yet does an admirable job maintaining objectivity, especially when confronting some of Reed’s episodes of cruelty, violence, and pettiness, while balancing those with positive qualities of quiet tenderness and mentorship he often showed, especially toward the end of his life.

DeCurtis does get a bit carried away when praising Reed’s body of work, however. It’s a stretch, for example, to call a so-so song like “Doing the Things that We Want To” off the New Sensations album a “masterpiece.” It’s not even the best song on the album.

DeCurtis, or an overzealous marketer writing the press release accompanying the book, also claims Reed was “an icon whose influence on popular music was rivaled only by that of Bob Dylan, James Brown, and the Beatles.” Hmm. Did anyone check with the estates of Elvis Presley or Jimi Hendrix, to name but two with stronger claims to that exalted status?

The rock journalist is also guilty of what we might call “insider trading” when praising a song whose backstory he has special knowledge of. His proximity to the music might give him a perch from which to better appreciate it, but the rest of us just listen to it as a song. Maybe it’s good. Maybe it’s not. We didn’t get to chat about it with Reed backstage before a gig or hang out with the woman it may or may not have been based upon.

On balance, though, DeCurtis gives us a compelling bird’s-eye view of an amazing life. After decades walking on the wild side of New York City, Reed sought domestic succor with Anderson on Shelter Island. Though he’d traveled far and wide literally and emotionally, the rock-music trailblazer ended his life quietly not far from where he started.

Google Maps says it’s about 84 miles from Freeport to Shelter Island. In their own way, Reed, “Reed,” and biographer DeCurtis understand it was a much longer journey.

Michael Causey frequently writes about music, and is the co-host of the Monday-morning program Get Up! on WOWD 94.3 FM Takoma Park, takomaradio.org