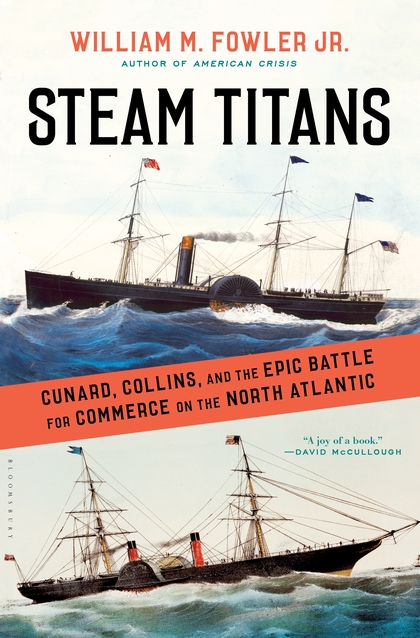

Steam Titans: Cunard, Collins, and the Epic Battle for Commerce on the North Atlantic

- By William M. Fowler Jr.

- Bloomsbury USA

- 368 pp.

- Reviewed by Jennifer Bort Yacovissi

- August 21, 2017

The decades-long fight for supremacy between two mammoth freighter lines.

Once upon a time, a New York businessman who understood the value of showmanship was wildly popular throughout the U.S. — having successfully branded his empire as a patriotic show of American superiority — but his success depended almost entirely on continual Republican support in a starkly partisan Congress.

In the end, he died penniless and forgotten, his family feuding bitterly for years over the scraps of his ruined estate, all sides refusing even to shell out the money for a gravestone.

I’m almost certain there’s an object lesson in there somewhere.

I speak, of course, of Edward Knight Collins, king of the U.S. Atlantic steamship trade. Not ringing a bell? Exactly. Contrast that with the enduring name recognition of his sole competitor, Samuel Cunard, of the eponymous Cunard Line, which continues today to bespeak luxurious ocean cruising.

Not bad considering that during their head-to-head competition in the mid-19th century, Cunard ships were known as dependable but damp, cramped, and thoroughly utilitarian, while Collins’ line was the lavish, spare-no-expense, debt-laden favorite of the overly privileged.

Author William M. Fowler Jr. knows his way around ocean-going vessels of bygone eras, with such previous scholarly books as Jack Tars and Commodores: The American Navy, 1783-1815, and America and the Sea: A Maritime History. His interest in the particular slice of maritime history profiled in Steam Titans appears to have been piqued when he took the first of many cruises aboard the Cunard-operated Queen Mary 2 as a guest lecturer in 2007.

Fowler takes us back to the shipping industry of Britain and the freshly declared independent American colonies to illustrate the formation and growth of trade routes and commodities, maritime law, and the U.S. merchant marine, as well as the often-prickly relationship between national politics and commercial interests.

After the War of 1812, commerce between America and Britain exploded, opening vast opportunities for those who could reliably ship goods between New York and Liverpool. The first transatlantic sailing packet ships began their runs in 1818.

Edward Collins grew up with his father, Israel’s, small coastal packet-shipping company, which made the regular run from New York to Charleston. After Israel made a string of bad business choices, Edward took over the imperiled family business, with big plans for expansion.

By 1840, his “Dramatic Line” of sailing packet ships was regularly transiting the Atlantic carrying goods and well-heeled passengers, and had made him wealthy and famous. But then he caught “steam fever” and realized that sailing ships were passé. “[It] is steam that must win the day.”

The Cunards of Philadelphia found themselves refugees resettled by the British in Halifax, Nova Scotia, at the end of the Revolutionary War, having backed the losing side. Samuel’s father invested wisely, and his son continued that course of diverse investments in solid ventures, including shipping. Then Samuel won government contracts to ship mail and tea — two crucial cargoes — and began to expand his growing empire, including into steam ships.

While early steam engines were a boon to river and coastal shipping on both sides of the ocean, a host of technical and economic challenges made their use in the transatlantic trade impractical. Every element of the enterprise cost more than sail, from the need for skilled mechanics to the fact that the machinery and coal made a steamship both far heavier and able to carry less paying cargo than a comparable sailing packet.

Even when improvements made steaming across the ocean more possible, nothing made it profitable. Both Collins and Cunard relied heavily on subsidies from their respective governments to remain afloat. This reliance put Collins on chronic tenterhooks; his livelihood was perpetually one no-vote away from disaster.

Interestingly, though they played up their competition — most aggressively in who made the fastest crossings — and the nationalist America vs. Britain angle, Collins and Cunard also had a secret agreement to ensure that one did not undercut the prices of the other.

Collins’ endless push to make headlines with record-setting crossings, no matter the weather or circumstances, ended in disaster. The 1854 sinking of the Arctic after a North Atlantic collision in heavy fog with a French fishing vessel played out like a preview of the Titanic, only with greater cowardice: “Of the approximately 400 people aboard, only sixty-one crew and twenty-four passengers had survived: not a single woman or child was among them.” Among the dead were Collins’ wife, two of his children, and his brother-in-law.

In 1856, in a race to embarrass the Cunard steamer Persia on her maiden voyage, Collins’ Pacific simply disappeared with 186 aboard, presumably after colliding with an iceberg or being crushed in a field of ice. Collins’ always-tenuous Congressional support disappeared, and he was finished.

That was the end of U.S. passenger ships. “By 1870, there was not a single American-flag passenger liner on the North Atlantic, nor were there any under construction, nor were there any being planned.”

Fowler’s epilogue offers the coda to this tale, a fine demonstration of the Law of Unintended Consequences: In their quest to support American shipbuilding, Republican Congresses would not allow ship owners to buy foreign-built ships, or even to buy back U.S.-built, foreign-bought ships to return them to American registry.

At the same time, high tariffs imposed on imported materials, meant to protect the iron and steel industries, simply succeeded in making ships too expensive to build in the U.S. Neither able to build local nor buy foreign, American shipping interests plummeted.

“Today, although most of American commerce moves by sea, only 1 percent is carried in American ships, nor is there a single American-flag passenger vessel or cruise vessel registered in international service.”

I believe we have discovered the object lesson.

Jennifer Bort Yacovissi’s debut novel, Up the Hill to Home, tells the story of four generations of a family in Washington, DC, between the Civil War and the Great Depression. Jenny is a member of PEN/America and the National Book Critics’ Circle, and writes and reviews regularly for the Independent as well as the Historical Novels Review of the Historical Novel Society.