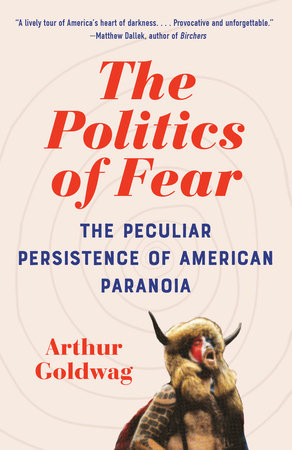

The Politics of Fear: The Peculiar Persistence of American Paranoia

- By Arthur Goldwag

- Vintage

- 304 pp.

- Reviewed by C.B. Santore

- April 22, 2024

From Pizzagate to QAnon, conspiracy theories are nothing new.

There are distinctions among conspiracies, theories about conspiracies, and conspiracy theories, according to Arthur Goldwag. Some conspiracies are true; for example, there was a conspiracy to assassinate President Abraham Lincoln and his top-ranking cabinet officials. Others are blatantly false; see “the Big Lie.” Facts are what separate proven conspiracies from the theoretical. In their absence, what escalates theories about conspiracies into full-blown conspiracy theories is paranoia.

The thesis of Goldwag’s The Politics of Fear is that there has been a strain of paranoia infecting American politics since the nation’s founding. The idea was most notably articulated by Richard Hofstadter in his essay “The Paranoid Style in American Politics,” which Goldwag references. The essay by the Pulitzer Prize-winning historian was published in Harper’s Magazine in November 1964 and is well worth reading.

Goldwag’s work is an extended, somewhat rambling rehash of Hofstadter’s piece, bringing us up to the present. It covers a lot of ground, ranging from numerous historical examples of conspiracy theories to the psychology that propelled them and the political contexts in which they were deployed. The book’s cover features a memorable character — dressed in headgear sprouting horns — from the January 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol and indicates where all this is leading.

How things got to that point on January 6th can be traced to several divisive factors that Goldwag says breed anxiety and foment conspiracy theories. His argument, similar to what Hofstadter noted, points to regional, religious, racial, and ethnic divides, though Goldwag adds increasing income inequality to the list. These divisions, like geological faults, are underlying fissures in American society that can rupture when stressed.

Impulses that had remained just below the surface have boiled over in a froth of hate and sometimes violence many times in our history: witch hunts in colonial America; anti-Illuminati and anti-Masonic fervor in the early 1900s; anti-immigrant-fueled conspiracy theories in the latter part of the 20th century; the Red Scare of the 1950s; and anti-Catholic and antisemitic sentiment throughout.

Goldwag uses historical examples such as these as background to the most consequential part of his book. What he really wants us to pay attention to is the current state of our politics. The same undercurrents that fueled conspiracies of the past are at work now, he warns:

“The great mystery today is not why a deracinated few still cling to their hateful delusions, but why the many are as susceptible to those delusions as they are.”

The author points a finger at politicians on the extreme Right. While acknowledging that the Left is not without its failings, some of which have lent credence to complaints from the opposition, he sees an existential threat coming from the Right. Politicians, either as true believers or cynical manipulators, are exploiting societal divisions to their own ends, egging on the us-against-them mentality among their followers, and inciting fear that “real” Americans and their values are under siege.

The title of Goldwag’s book correctly emphasizes fear. Conspiracy theories that reinforce fear are easy to believe given our psychological propensity to tune out what conflicts with our gut instincts. Cognitive dissonance, projection, and confirmation bias (what Hofstadter called “psychic phenomenon” before these terms entered the vernacular) undermine facts, creating confusion and mistrust that help a conspiracy theory grow. Politicians are able to exploit fear because it isn’t fact-based, the author contends. It’s about feelings.

Even more worrying to Goldwag is the overlap he sees of authoritarian leadership and the cult-like worship of a single savior. Conspiracy promoters conjure such devastating outcomes that devotees come to believe only a divinely inspired leader working as an instrument of God can save them. In Hofstadter’s words:

“The paranoid spokesman sees the fate of conspiracy in apocalyptic terms.”

The book does an adequate job of explaining the genesis and persistence of paranoid politics and sheds light on why so many are so susceptible, but except for the updated references to MAGA politics, nothing here is new. It all sounds very much like Hofstadter: “American politics has often been an arena for angry minds. In recent years we have seen angry minds at work mainly among extreme right-wingers.” The recent years Hofstadter was referring to were the 1950s and 1960s.

The failing of The Politics of Fear is that re-explaining a phenomenon’s causes does not suggest a remedy. The question of what we can do about it remains unanswered. Logical argument is not the antidote to conspiracy theories because our febrile politics are more about identity than ideas. Human nature being what it is, it’s unlikely we can stamp out anxiety or change our psyches. “The interplay of conspiracy theories, the paranoid style, and the status anxieties that are at their roots are as old as humanity,” Goldwag concedes.

Perhaps it’s unfair to fault Goldwag for lacking originality or a more concrete answer to such a perplexing, persistent dilemma. If his book sounds an alarm that motivates even a few, it will have been worthwhile. And the alternative — waiting out the cycle and hoping the ship of state rights itself, as it has in the past — risks the contagion spreading further. “In the end,” Hofstadter concluded, “the real mystery, for one who reads the primary works of paranoid scholarship, is not how the United States has been brought to its present dangerous position but how it has managed to survive at all.”

C.B. Santore is a freelance writer and editor in East Hampton, CT.