The writer talks resilience and the steadfastness of women on the home front.

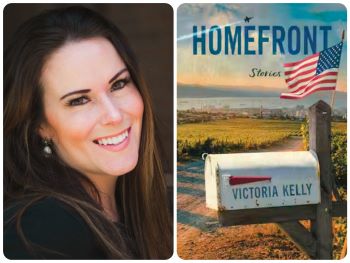

In her sparkling and thoughtful new collection of short stories, Homefront, author Victoria Kelly imagines the inner worlds of women whose lives have been impacted by war and military service. As the former wife of a fighter pilot, Kelly knows whereof she writes. And even though these stories are pure fiction, it’s hard not to imagine her living out every scenario, from the Navy wife who discovers her neighbor is having an affair while their husbands are deployed to the woman who divorces her serviceman husband and starts over as a movie star.

Kelly, whose last novel, Mrs. Houdini, imagined the life of magician Harry’s wife, is also a poet. Her lyricism is evident in all 14 stories in Homefront. A woman’s hair caught in the wind is “blown up like a candelabra.” Floors in a building slope “like the backs of old men.” The fall trees in Maine are “scalded with color.” She talks about the collection here.

I know a bit about your first marriage, so I’m wondering what stories in this collection are closest to your own experience as the wife of a fighter pilot.

None of the characters in the book are based on real people. But I relied a lot on my experiences with real places (like bases in Florida and Virginia Beach) and real scenarios that spouses in general face. The story “What Happened on Crystal Mountain” is the closest to anything I really experienced. Back then, Navy fighter pilots started their training in Florida on the T-34, a single-engine propeller plane. A lot of the planes were really old — decades old. When I was dating my first husband, one of the student pilots he was training with crashed into a mountain during a training flight, and he didn’t survive. It was my first experience with how dangerous flying is. Most accidents happen during training, not in combat. All of that became a reality in that moment. You think, “It could have been anyone.”

As a writer, I think it’s really hard to sustain the second-person voice. What went into your decision to write “All the Ways We Say Goodbye” in that tense?

This was the first story I wrote for this collection, and it’s always been special to me. I was inspired by a short story by Maile Meloy, “Ranch Girl,” that she wrote in second person. On the surface, it’s about a girl in her 20s who takes in her father’s cocker spaniel after he passes away (her mother, a military nurse, abandoned the family when she was young). She is dealing with the grief of knowing the dog is sick and has to be put down, but really she’s dealing with the loss of her father — and the sadness of knowing that she can’t ever get back her old life. The first sentence in the story is, “When you grow up in New Jersey, in the dim gray suburbs of New York, you grow up with the knowledge that one day you will have to leave.” That was the first sentence I wrote. Most people in my high school left the state for college. New Jersey was kind of a launchpad for their “next lives.” I was drawing on the idea that once you leave, you probably won’t go back, and even if you did, it wouldn’t be the same.

How did you arrange the stories? Did you always know, for example, which one would kick off the collection and which one would end it?

I didn’t write them in order. I put “Finding the Good Light” first because it’s about a divorced pilot’s spouse who is discovered by a Hollywood director — and I just love that look into the glitzy world of celebrity, so I wanted that to go first. The next story, “Prayers of an American Wife,” is really the heart of the book. It’s based in Virginia Beach, where I spent eight years and went through three deployments. And it covers a lot of the emotions military spouses go through during those times. After those, I tried to alternate between the ones that are directly about the military life and those that only touch on it briefly. Because it’s a lot about the military, but really it’s a book about women in general looking for somewhere to call home.

How do you know when it’s time to end a story? (This came up particularly in “A Home Like Someone Else’s Home.” Why did you decide to end it where you did?)

So much of “A Home Like Someone Else’s Home” is based on a real experience. It’s about a young woman working in a law office in Iowa who is representing a Bosnian man who is about to be deported. She goes to visit him in an immigrant-detention center. When I was at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, I volunteered for a human-rights organization, helping immigrants with legal issues. I visited a detention center (this was long before immigration became a hot political issue) and met a man just like the character in the book. I felt like I had to end that story where I did, and leave it open-ended, because I never knew what happened to him in the end. These cases go on for years. But I have never forgotten him.

Sometimes, novels grow out of short stories. Do you plan on expanding anything in the collection?

For the most part, I think these stories are destined to be as they are in the book. But if I was going to turn one into a novel, I think it would be “Finding the Good Light.” There is so much potential there — a woman who goes from being the supporting character in her husband’s “glamorous” life as a fighter pilot to being famous in her own right. I think every woman has had that fantasy of being “discovered,” and what that would look like, so it’s fun for me to go into that world.

[Editor’s note: Victoria Kelly will be in conversation with Karin Tanabe at Kramers in Washington, DC, tonight at 7 p.m. Learn more here.]

Cathy Alter is a member of the Independent’s board of directors and the author, most recently, of CRUSH: Writers Reflect on Love, Longing, and the Power of Their First Celebrity Crush.