A recent biography reveals James Ellroy to be every bit as over-the-top as his hardboiled detectives.

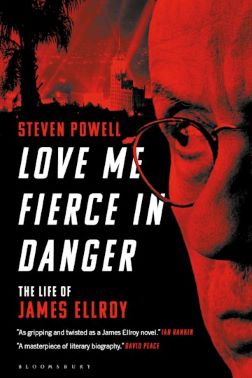

Just when the reader thinks she’s seen it all in the sexist, racist, homophobic, violent, and murderous figures who populate James Ellroy’s fiction, along comes this biography of the self-described “demon dog” of crime novels. Ellroy’s back-from-the-brink life story rivals that of his characters. Steven Powell’s Love Me Fierce in Danger (the title taken from an inscription Ellroy wrote on the back of a photo of one of his ex-wives) describes Ellroy’s youthful descent into an abyss of alcoholism, drug abuse, crime, jail, mental illness, and homelessness and is a must-read for his fans.

Powell has made something of a career of chronicling Ellroy’s career. His blog has a section dedicated to Ellroy with more than 100 posts. Ellroy and Powell met in 2009 when the latter was a graduate student and Ellroy’s oeuvre was his thesis topic. Ellroy showered the young academic with unexpected attention, and Powell repaid him by dedicating the next decade to writing three books about Ellroy’s work. Notwithstanding their relationship, Love Me Fierce in Danger is no fawning exercise in hero worship. Instead, it is an insightful, no-holds-barred examination of what makes the strange author of The Black Dahlia, L.A. Confidential, White Jazz, My Dark Places, and other books tick.

Ellroy appears at his literary events in a loud Hawaiian shirt and aims to shock his book-buying audience. “Good evening, peepers, prowlers, pederasts, panty sniffers, punks and pimps,” he often begins. “I’m James Ellroy, demon dog of American literature, the foul owl with the death growl, the white knight of the far right, and the slick trick with the donkey dick.”

And so on.

He began life in 1948 as Lee Earle Ellroy — a name that sounds like it came straight out of the trailer park. But in fact, Ellroy and his parents, Jean Hilliker, a nurse, and Armand Ellroy, a tax preparer for Hollywood types including Rita Hayworth, lived a comfortable life (despite the adults’ raging alcoholism) in West Hollywood until a bitter divorce pushed Lee and his mother into a downscale neighborhood in El Monte.

Young Lee blamed his mom for the family break-up and wished her dead. He got his wish on June 21, 1958, when, while on a date with an unknown man, Jean was sexually assaulted and strangled to death. Her killer was never found. Jean’s murder took place slightly more than a decade after the infamous, unsolved torture-murder in Los Angeles of Elizabeth Short, dubbed “the Black Dahlia.” The cases would be forever entangled in Ellroy’s head and provide the macabre inspiration for his long and successful writing career.

Jean’s death derailed Lee’s childhood and left him with his lazy and inattentive father. Papa Ellroy didn’t housebreak the family dog, ensure his son attend school, or stop the boy from goosestepping around dog droppings while espousing pro-Nazi ideologies at home. A misfit at Fairfax High in West Hollywood, Ellroy handed out hate tracts to fellow students and attended a Nazi rally where he sang the Horst Wessel song. Eventually, his racist rants got him expelled.

With nothing better to do, Ellroy shoplifted, peeped through bedroom windows, and made obscene phone calls. He joined the Army on the cusp of the U.S. troop escalation in Vietnam, instantly regretted it, and feigned insanity to score a discharge. As his father lay dying soon after, Ellroy claims the old man’s last words to him were, “Try to pick up every waitress who serves you.”

Ellroy wasted the next decade breaking into homes in upscale Hancock Park to steal food from refrigerators and the panties of girls who attracted him. Only the Manson Family murder of actress Sharon Tate on August 9, 1969, made him stop; beefed-up neighborhood security left him in fear he’d be arrested or killed. There was binge-drinking and drugging (Seconal, Nembutal, Dexedrine, and Romilar cough syrup stolen from the drugstore). His sexual activity consisted of masturbating for hours. Between 1968 and 1975, Ellroy was arrested no fewer than 15 times (although he’d brag of as many as 70 arrests) for shoplifting, burglary, drunk driving, and indecent exposure.

In and out of jail and living on the streets and in flophouses, it wasn’t until he suffered seizures, hallucinations, and blackouts from alcohol-withdrawal syndrome (the DTs), as well as a dangerous lung abscess, that Ellroy turned his life around. “He joined Alcoholics Anonymous at the age of twenty-seven and, barring a couple of relapses, has been sober ever since,” writes Powell. “But the addictive side of his character remains in everything from his unyielding ambition, voracious appetite for women, right down to the copious amounts of coffee he consumes daily.”

After sobering up, Ellroy snagged a job as a golf caddy through a fellow Skid Row hotel tenant. Drink and drugs were replaced by insomnia, God, conservative political leanings, ceaseless reading, and a desire to write. One woman called to him like a siren: the Black Dahlia. Unfortunately, John Gregory Dunne beat Ellroy to the subject in 1977 with the bestselling novel True Confessions.

On January 26, 1979, Ellroy finally sat down to write (in longhand) the opening line to a different first novel, Brown’s Requiem: “Business was good. It was the same thing every summer.” And so began a now 45-year career. He paid a friend to type his finished manuscript and sent it to the only four agents in Writer’s Market who indicated they’d read unsolicited material. He gave himself a new name, “James Ellroy.” Avon bought the book for $3,500, and Ellroy blew the advance on back rent, a 1964 Chevy Nova, a cashmere sweater, and a weekend jaunt to Santa Barbara with a girlfriend.

Many other books — including his own about the Dahlia killing, which became his first bestseller — followed. His relationships with women, tangled up as they are with Jean Ellroy’s horrifying murder and the impact it had on her 10-year-old son, are complicated, to say the least. He used the real name of one of his ex-girlfriends as the name of a dead hooker in L.A. Confidential. His parting gift to his ex-wives and girlfriends has been to dedicate his books to them.

Divorced from his second wife, Helen Knode (to whom he wrote the inscription which provided the title for this biography), since 2006, Ellroy moved to Denver in 2016 to live in an apartment down the hall from her, an arrangement that seems to be the answer to domestic tranquility for both of them. But despite his best efforts, he hasn’t found the answer to the question that has shaped his career as well as his life: Who killed his mother, and why.

Diane Kiesel is a former judge of the Supreme Court of New York. She is an author whose next book, When Charlie Met Joan: The Tragedy of the Chaplin Trials and the Failings of American Justice, will be published later this year by the University of Michigan Press.